(Date – Parody By: “Parody Title,” Length.)

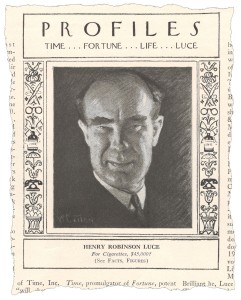

- January 1937 – Penn State Froth: “Froth,” 1 page + front cover.

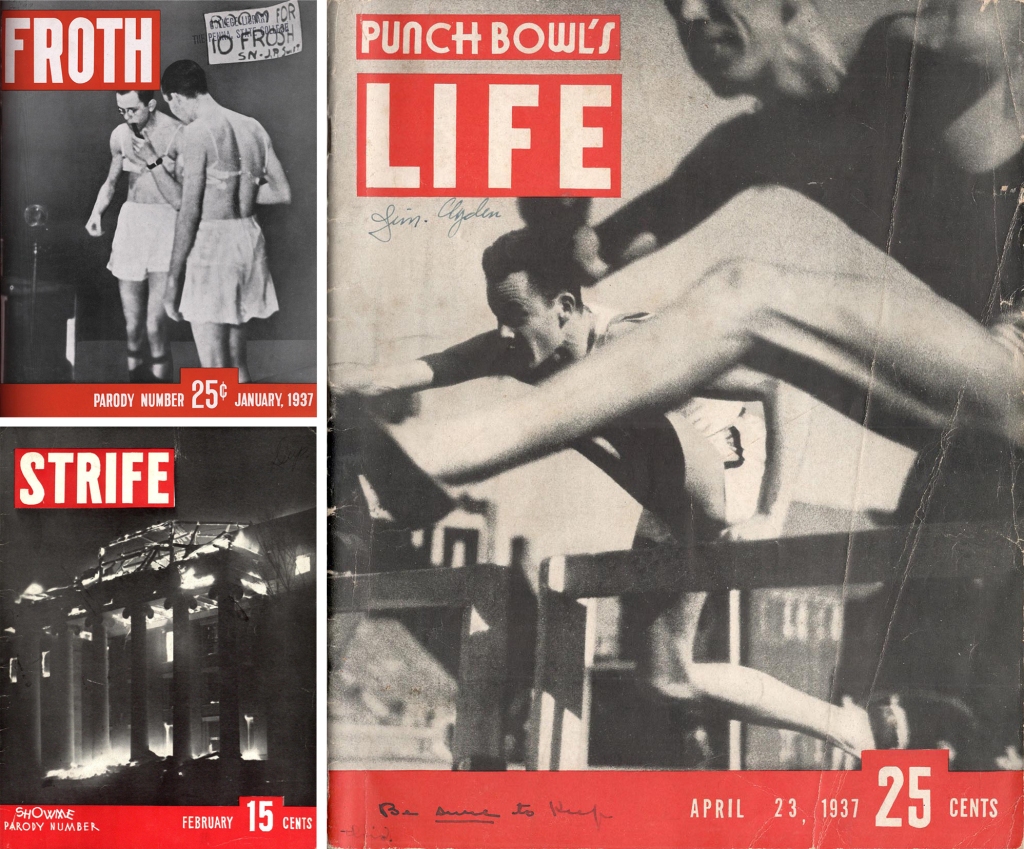

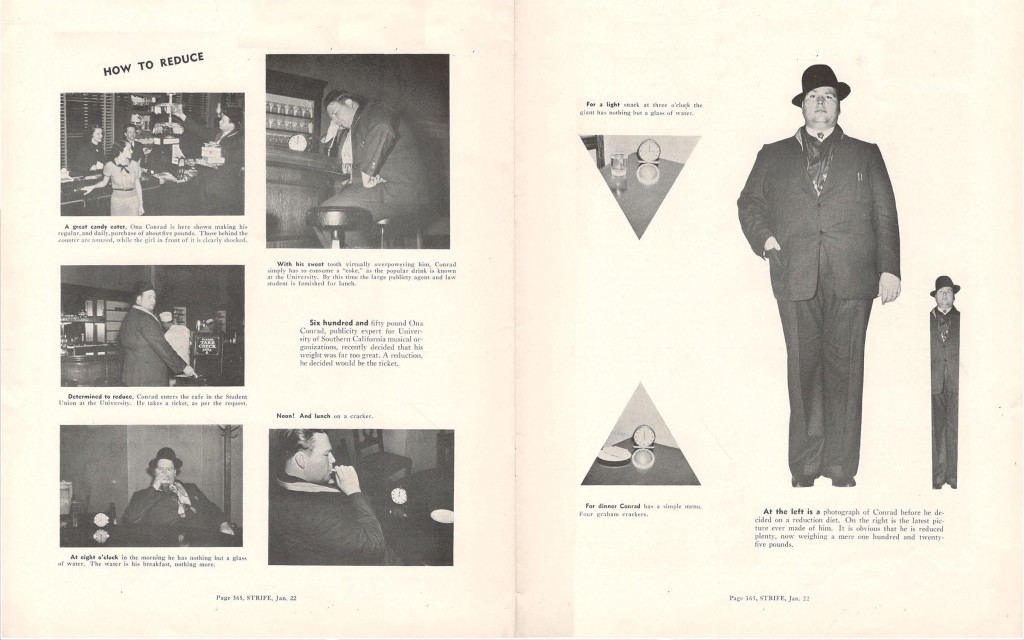

- January 1937 – USC Wampus: “How to Reduce” (article from “Strife”), USC Wampus, 2p.

- February 1937 – Missouri Showme: “Strife,” 24p + 4c.

- April 23, 1937 – Pennsylvania Punch Bowl: “Punch Bowl’s Life,” 56p + 4c.

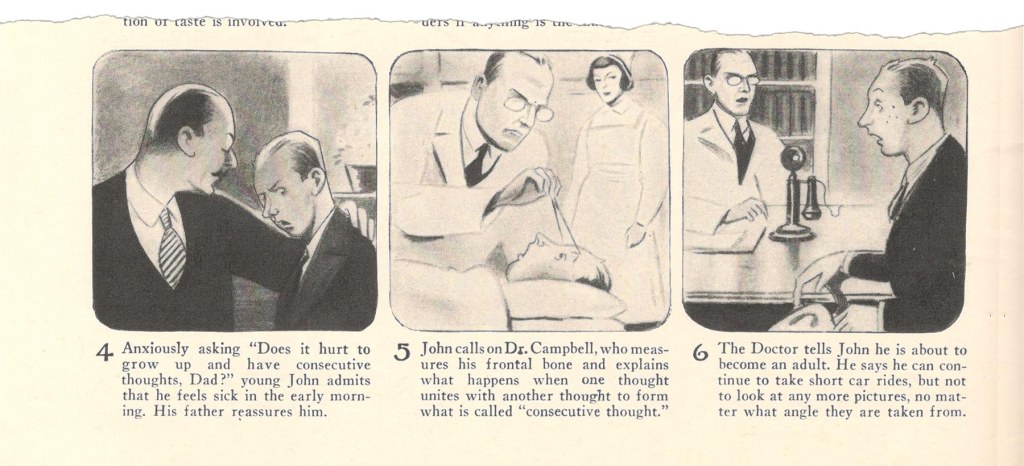

- April 23, 1938 – The New Yorker: “The Birth of an Adult” (article), 2p.

- January 1939 – Penn State Froth: “Life Goes to a Froth Party” (article), 1p.

- November 1939 – Wisconsin Octopus: “Life Discloses The Happy Weekend of a Wisconsin Coed” (article), 1p.

- December 13, 1940 – U.S. Naval Academy Log: “Log,” 64p + 4c.

- March 5, 1941 – Ohio State Sundial: “Life Comes to Ohio State” (article), 2p.

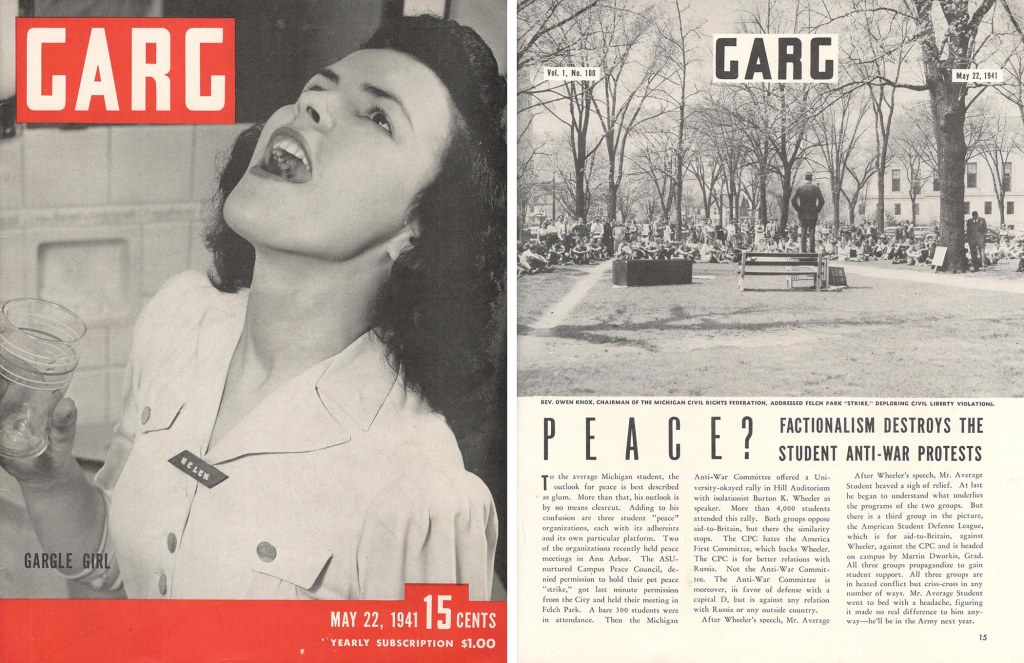

- May 5, 1941 – Michigan Gargoyle: “Garg,” 52p.

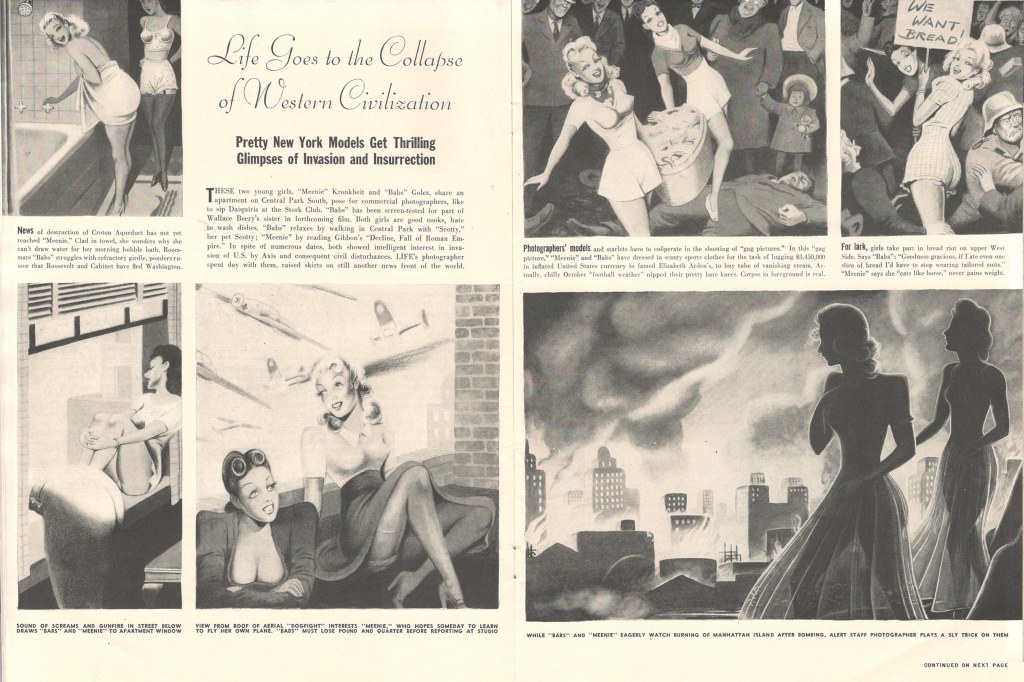

- October 25, 1941 – The New Yorker: “Life Goes to the Collapse of Western Civilization” (article), 3p.

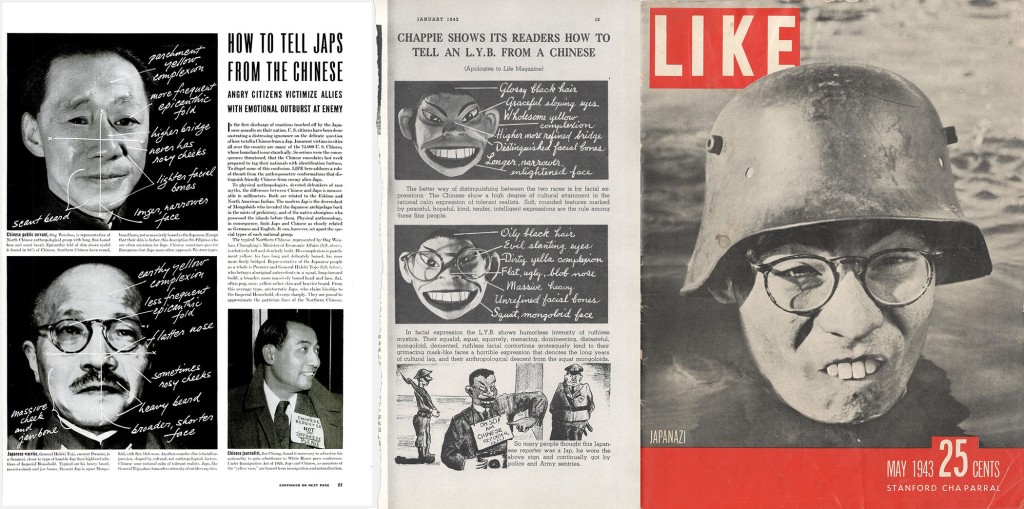

- January 1942 – Stanford Chaparral: “…How to Tell an L.Y.B. from a Chinese” (article), 0.67p.

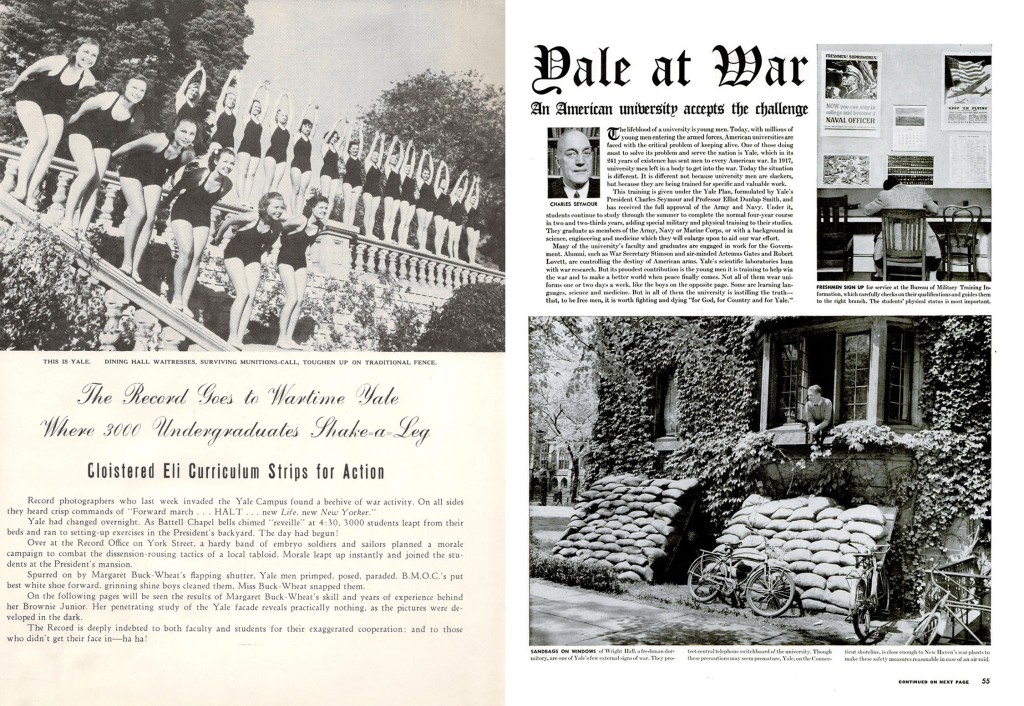

- May 20, 1942 – Yale Record: “The Record Goes to Wartime Yale” (article), 5p.

- October 1942 – Penn State Froth: “Life Goes to Penn State” (article), 2p.

- May 1943 – Stanford Chaparral: “Like,” 32p + 4c.

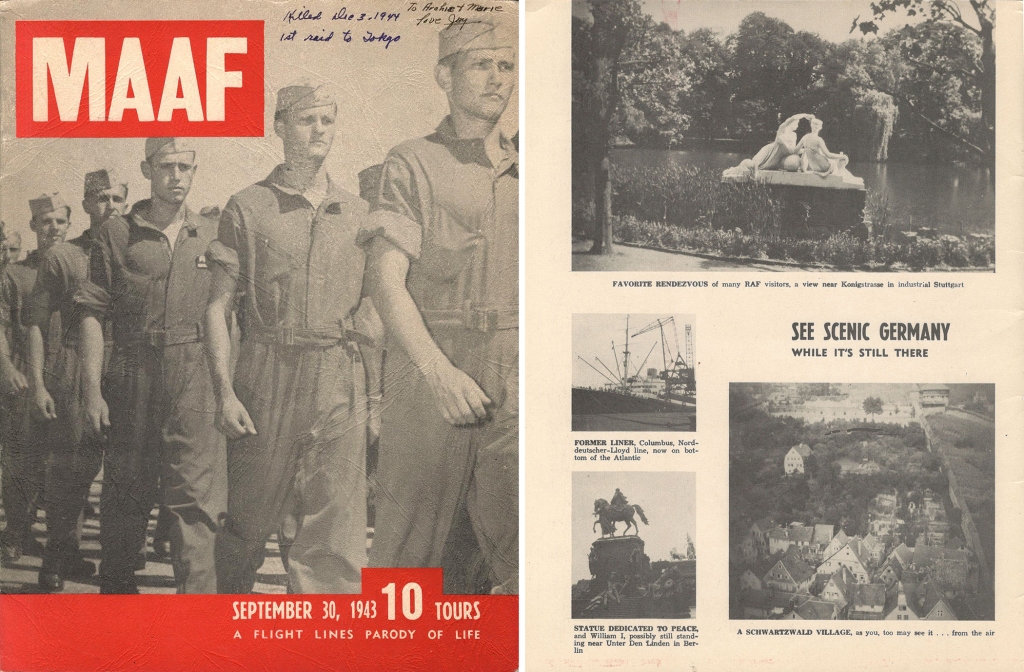

- September 30, 1943 – Merced Army Air Field Flight Lines: “MAAF,” 44p + 4c.

- Fall 1943 — German Ministry of Propaganda, “Life/Life?” (leaflet/poster), 8p on 2.

- February 25, 1944 – U.S. Naval Academy Log: “Log,” 56p + 4c.

- Fall 1944 — German Ministry of Propaganda, “Life/Death” (leaflet), 2p.

- February 23, 1945 – U.S. Naval Academy Log: “Log,” 44p + 4c.

The most famous parody Life inspired wasn’t a parody of Life. The first issue of Time Inc.’s picture weekly was still on the stands in 1936 when The New Yorker published Wolcott Gibbs’s Profile of publisher Henry R. Luce. Written entirely in backward-running, multi-adjectived early Timestyle, “Time … Fortune … Life … Luce” exposed the inner workings of man and mags in intimate detail, memorably ending, “Where it all will end, knows God!” Luce suspected the story might be payback for a similar vivisection of The New Yorker in Fortune two years earlier, but he cooperated to promote Life. He was furious when New Yorker editor Harold Ross showed him an advance copy, and when Luce was furious, he stuttered.

“Goddamn it, Ross, this whole goddamned piece is ma-ma-malicious, and you know it!” he said when the two sides met at Ross’s apartment just before publication.

“You’ve put your finger on it, Luce,” Ross replied; “I believe in malice.”

Luce could have spared himself the heartburn. With or without The New Yorker’s blessing, Life was going to be a hit. The development of sharper, smaller cameras in the early ’30s had sparked a boom in candid news photos and inspired successful large-format picture weeklies in Europe. For Time Inc., which was already exploring photojournalism in Fortune and The March of Time, it was a natural next step.

Early on, in-house experts projected Life might sell 250,000 copies a week, total; it reached 235,000 in advance subscriptions alone. When the first issue went on sale on November 19, 1936, the Thursday before the cover date, all 200,000 newsstand copies disappeared that day. “The demand for Life is completely without precedent in publishing history,” circulation manager Pierre Prentice wrote, “There is no way we could anticipate a bigger newsstand business in the first month than magazines like Collier’s and Satevepost have built up in thirty years.” By the end of its first year, Life’s circulation was 1.5 million; six months later it passed 2 million.

Success spawned imitators and parodists. The commercial ripoffs favored cheap paper and punchy titles like Click, Pic, Spot and Dash. Most were “edited with the viewpoint of a circus sideshow – heavy on cheesecake and the freakish,” Robert Elson wrote in Time Inc.’s official history. (Only Gardner Cowles’s Look lasted, and it was in the works before Life debuted.) Life-like photo spreads began to appear in annual reports and house organs, and picture magazines sprang up on campuses from UCLA to Dartmouth. College humor mags added photo pages; at least one, the M.I.T. Voo Doo, changed its whole personality: “It is no longer primarily a humor magazine, . . . because college humor magazines in general are a mistake,” school paper The Tech sniffed in May 1939. “The substitute . . . bears a resemblance to the magazine, Life, but it is a well done resemblance, and does the resembler credit.” Fortunately, the comic spirit proved unkillable, and Voo Doo was soon its discreditable old self.

The Southern Cal Wampus and Penn State Froth pounced on Life at once, getting brief spoofs into parody issues already scheduled for January 1937. Froth was first to run a fake Life cover, but the first issue-length takeoffs were the Missouri Showme’s “Strife” in February and “Punch Bowl’s Life” at Penn in April. Their haphazard layouts and tiny photos look crude now — they looked crude then — but they’re only slightly worse than some of the real thing’s early pages.

Like Punch Bowl’s, most college “Lifes” were less parodies than small-scale emulations, set in a world that ended at the campus gates. Some had so much fun pretending to be Life they neglected to make fun of it: “Strife’s” headline calling nearby Stephens College for women “A Shining Pearl in U.S. Educational Diadem” isn’t sarcasm but the intro to a five-page puff-piece. The Michigan Gargoyle’s “Garg” raised eyebrows in 1941 with its open-throated cover girl, but the lead story on a campus antiwar rally is straight reporting, as is most of what follows. Other emulations mixed factual local features with spoofs of the outside world. A few dispensed with jokes entirely — an understandable decision for the Naval Academy Log in 1944 and ’45, if not for a civilian comic in peacetime.

Students who had seen the story-making machinery up close were less respectful. After visits from Life crews in 1939-42, the humor mags at Wisconsin, Ohio State and Yale all mocked them for missing the dullness and/or debauchery behind the ivy-covered facades. The Yale Record was confident enough to send its five-page spoof to press weeks before “Yale at War” appeared in Life’s June 6, 1942, issue: The creators badly overestimated the number of swimsuits the real story would display. But such cynics were exceptions: Life wanted be liked, and in the ’30s and ’40s it was often copied but seldom mocked.

Except at The New Yorker. Relations had started badly in 1925, when two-year-old Time panned The New Yorker’s first issue. They grew worse after Ross’s right-hand man Ralph Ingersoll defected to Luce and aired Eustice Tilley’s underthings in Fortune. (The story ran without a byline, but all concerned knew.) History aside, the understated, unflappable New Yorker and bubbly cheerleader Life were never going to be besties. In 1938, when Life made headlines and risked bans with four pages of stills from an educational film on childbirth, The New Yorker’s E.B. White and Carl Rose responded with “The Birth of an Adult.” One key to maturity, they insisted, was giving up pablum like Life. An early-’40s Garrett Price cartoon was more succinct: “Is it okay, Joe,” one ad copywriter asks another under a wall of Life covers, “to refer to our subscribers as readers?”

The harshest blow was “Life Goes to the Collapse of Western Civilization,” by Russell Maloney and Rea Irwin. Published shortly before Pearl Harbor, the three-page pictorial leeringly followed two attractive models around Manhattan as New York fell to Axis invaders. “Harold Ross, always glad to tweak what he considered the pomposity of Luce and his magazines, took note of Life’s simultaneous fascination with ‘pretty women’ and its doomsday fantasies as it attempted to prepare its readers for war,” Alan Brinkley wrote in his biography of Luce. “Luce had reacted to The New Yorker’s satirical 1936 profile of him with almost violent fury. But by 1941 he was so deeply immersed in the cause of the Allies that he gave The New Yorker, and his other critics, virtually no notice at all.”

Life’s first issue after the U.S. entered World War II contained one its most embarrassing editorial missteps: a two-page primer on (literal) racial discrimination called “How to Tell Japs From the Chinese” (Dec. 22, 1941). The Stanford Chaparral responded in January 1942, pushing Life’s loaded adjectives and wispy distinctions to absurdity in “How To Tell an L.Y.B. From a Chinese.” Its casual use of racist language to express anti-racist sentiments wouldn’t fly today, but it’s a time capsule of Stanford’s mood in the months between Pearl Harbor and the internment orders, when a thirst for vengeance against Japan mixed with concern for the feelings and safety of Japanese-American fellow students (of whom there were around 30 at Stanford in 1941-42). Significantly, though the issue is called the “L.Y.B. Number,” the phrase “little yellow bastards” never appears, and the writing steers away from the kind of vituperation mocked in “How To Tell… .” (The cartoons are a different story, as usual.)

Chappie’s “Like” in May 1943 also wobbled between crudity and restraint. The face on the cover is the standard buck-toothed, four-eyed stereotype (though in a German helmet), but the story inside says nothing about the physical appearance or innate viciousness of the enemy “Japanazis.” The battle to oust them from a bridge in nearby Vallejo is a bloodless romp that only ensures “a quarter million free Luckies . . . reached our Boys overseas.” Other stories put comic spins on favorite Life subjects — the brilliant thinker who sounds like an idiot, the apple-cheeked teenager dating a drag racer — all of them located in and around Palo Alto.

The longest passage in “Like” that sounds even half sincere is an editorial regretting the “brilliant” idea of creating it in the first place: “This required changing our usual page sizes and make-up and produced general chaos and upheaval . . . . Not the least of our worries was the taking of the numerous pictures . . . [which] requires more time than filling a space of equal size with type.” The Chaparral wasn’t alone in finding Life hard to copy: Only the most meticulous editors had the time or skill to match its trademark squared-off text blocks and photo captions, which always ended with a full line of type.

Life’s war coverage pushed its circulation past 5 million and made it a worldwide symbol of U.S. power and influence. The staff of Flight Lines magazine at the Merced Army Air Field in California borrowed some of that glamor for its September 1943 cadet class book, using Life’s format to show that pilot trainees “do occasionally leave their work . . . to eat, to talk . . . to keep up on the events of the world and the war . . . or just to relax.” Opposite a fake ad inviting graduates to “See Scenic Germany — While It’s Still There,” the editors ran a letter from the real Life giving permission for the parody, as long as it didn’t have “a very close imitation of Life’s cover … [or] the word Life in a box as we use it … so there is no possibility of confusion.”

The memo didn’t reach German propagandists who dropped an eight-page leaflet/poster on U.S. air bases in East Anglia that same fall. “The front page was an actual reproduction of [the cover of] the true Life issue for July 26, 1943, with pictures of 8th Air Force crews,” R.G. Auckland and Kenneth B. Moore wrote in Messages from the Sky over Britain (London: Psywar Society, 1998), “but the remaining seven pages showed gruesome and horrifying pictures of aircrews who had been killed over Germany, together with many speeches, reports and quotations on the subject of the air bombing of the Third Reich. . . . No mention of the incident appeared in the contemporary national press.” (The whole gory thing can be seen at imgur.com/a/Y2w6u.) A few months after D-Day, postcard-size “Life” covers dated October and November 1944 cropped up in Italy: One one side, a nude woman posed under the familiar logo; on the other, a skull in an army helmet hovered between the red-boxed word “Death” and the date “Doomsday 1944.” At least six different photos were used on the nude side, while the skull alternated between British and American headgear.

“Though we did not plan Life as a war magazine, it turned out that way,” Luce once said. But while the World War II years were Life’s greatest era, the late ’40s and ’50s were its grandest. It was then that parodists outside The New Yorker turned their sights on Life itself, mocking not just the things it covered but the way it covered them. They’ll be the subjects of my next post. — VCR