College students will parody almost anything, but you can flip though hundreds of old campus humor magazines without finding a fake cigarette ad. You’ll find hundreds of real ones, though: From the 1920s until 1963, tobacco companies were the biggest national advertisers in U.S. college media. According to scholar Elizabeth Crisp Crawford, in the early ’60s “nearly 2,000 college publications, mainly newspapers, received nearly 50 percent of their advertising revenue from the tobacco industry.”*

The proportion was likely higher for humor magazines: Even the shoddiest campus chuckle-sheet typically had a four-color, full-page cigarette ad on its back cover, and a fat book like the Yale Record might run several more inside. The revenue from one such ad often covered an issue’s entire production cost. In return, prudent editors stifled the urge to crack jokes about cancer sticks. This quid pro quo normally went unspoken, but on the rare occasions it was violated Big Tobacco’s minions on Mad Ave. weren’t shy about reminding the kids who signed the checks. The only unusual feature of this 1960 dust-up involving L&M and the Stanford Chaparral is that the latter made it public.

L&M debuted in 1953 as Liggett & Myers’ entry in the fast-growing filter-cigarette category. The Surgeon General’s report was still a decade away, but already there was growing evidence linking smoking to lung cancer. The industry’s response was a flurry of filtered and mentholated brands pitched as “milder,” “cleaner” and “cooler” than traditional smokes; if customers assumed they were also safer, so much the better. By the late ’50s, the Big Three advertisers of previous decades — Chesterfield, Camel and Lucky Strike — had given way to L&M, Winston (born 1954), Salem (b. 1956) and a rebranded Marlboro (b. 1924 as a “woman’s cigarette,” butched-up in 1955).

L&M’s first Chaparral ad ran on the February 1959 back cover, a spot it held on six of the next eight issues. College Magazines, Incorporated, the New York agency that placed national ads in most campuses, normally supplied a fresh pitch every month, whether the product changed or not, but the January 1960 Chaparral reprinted the L&M ad from December. The “L&N” parody appeared in February, and in March editor Ray Funkhouser received a very unhappy letter from a College Mags account manager named Philip Knowles.

Knowles’ letter was published in the May 1960 issue. It packs so much sarcasm, condescension, realpolitik and bare-knuckle intimidation into a few hundred words that it deserves to be read in toto, but the highlight is surely the righteous disapproval of tasteless louts who “think remarks about cancer are funny.” In reply, the editors brazenly pled guilty as charged, then insinuated College Mags’ indignation had more to do with money than morality.

The kids had the last word in the argument, but Big Tobacco got the last laugh, just as Knowles predicted. The January 1960 Chaparral was the last to carry a real cigarette ad; for the rest of the school year, the usual back-cover client was local merchant Gleim Jewelers. In 1963, Big Tobacco “voluntarily” stopped advertising in campus publications as part of a last-ditch effort to head off federal legislation; the move failed to assuage the Feds but put the hurt on college newspapers and killed most of the humor titles. The Chaparral managed to survive, barely, but was never again as fat and profitable as it was in the ’50s. L&M, meanwhile, fell from 15 percent of the U.S. market in 1960 to less than 1 percent today, but in 2012 was the fourth biggest brand worldwide; it now spends almost all its advertising dollars overseas. — VCR

_______________________

* Elizabeth Crisp Crawford, Tobacco Goes to College: Cigarette Advertising in Student Media, 1920-1980, (McFarland & Co., 2014), p. 34. Most of the book is a detailed study of one newspaper, The Orange and White at the University of Tennessee. Crawford barely mentions college humor mags, but their rise and fall correlates perfectly with the ebb and flow of cigarette ads in the O&W: Both took off in the ’20s, held on through the Depression, dipped during World War II, came back strong in the late ’40s and flourished in the ’50s.

The Harvard Lampoon may be the source of the “annual” misapprehension. Early on, its parodies really did appear every year: 27 in the quarter-century from 1919 to 1943. (Here’s a

The Harvard Lampoon may be the source of the “annual” misapprehension. Early on, its parodies really did appear every year: 27 in the quarter-century from 1919 to 1943. (Here’s a

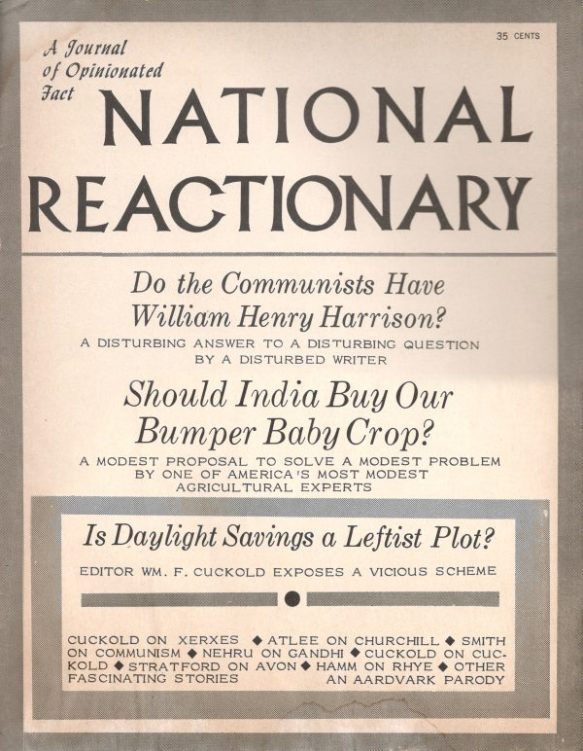

Aardvark was going to be the humor magazine at Chicago’s Roosevelt University until the Powers That Be saw the first issue. Shut out at home, founders Jeff Begun, Ron Epple and Howard R. Cohen decided to broaden their reach to all the city’s campuses. Aardvark survived for at least 11 issues (the last I know of is Vol. 3, no. 2, from 1964) and at its peak was distributed from Madison to Urbana. Its strengths were sharp writing and smart interviews with humorists including Mort Sahl and Shel Silverstein; its handicaps included cheap paper, sloppy layout and ugly columns of typewriter-font text.

Aardvark was going to be the humor magazine at Chicago’s Roosevelt University until the Powers That Be saw the first issue. Shut out at home, founders Jeff Begun, Ron Epple and Howard R. Cohen decided to broaden their reach to all the city’s campuses. Aardvark survived for at least 11 issues (the last I know of is Vol. 3, no. 2, from 1964) and at its peak was distributed from Madison to Urbana. Its strengths were sharp writing and smart interviews with humorists including Mort Sahl and Shel Silverstein; its handicaps included cheap paper, sloppy layout and ugly columns of typewriter-font text.

The Dartmouth Jack-O-Lantern‘s “Nü Yorker,” unlike the Purple Parrot‘s, is all fake and strictly for laughs, from Jerry Lewis’s letter to the editor (“I respectfully request … that neither my social security number, nor a photostat of my birth certificate be reprinted in any subsequent issues”) to the caption contest featuring Jacko‘s favorite running gag, “Stockman’s Dogs” (two canines drawn in 1934 and present in nearly every issue since). Notably funny pieces include “Letter From A Truck Stop Outside Neola, NE: This Place Sucks”; a deranged “Profile” of a poor guy named Jack Napier who can’t convince the author he’s not the Joker; and a wonderfully pretentious poem, “Skipping Cultural Stones on the Sea of Aspersions.”

The Dartmouth Jack-O-Lantern‘s “Nü Yorker,” unlike the Purple Parrot‘s, is all fake and strictly for laughs, from Jerry Lewis’s letter to the editor (“I respectfully request … that neither my social security number, nor a photostat of my birth certificate be reprinted in any subsequent issues”) to the caption contest featuring Jacko‘s favorite running gag, “Stockman’s Dogs” (two canines drawn in 1934 and present in nearly every issue since). Notably funny pieces include “Letter From A Truck Stop Outside Neola, NE: This Place Sucks”; a deranged “Profile” of a poor guy named Jack Napier who can’t convince the author he’s not the Joker; and a wonderfully pretentious poem, “Skipping Cultural Stones on the Sea of Aspersions.”