Punch (1841-1992) loved parody from birth, but it waited over a century to do a full-scale takeoff of another publication. The main holdup was its mid-Victorian layout, which left targets from The Yellow Book to yellow journalism looking very much like Punch. Big change only came in 1949, when art editor Kenneth Bird (a.k.a. the cartoonist “Fougasse”) became the first visual thinker to get the top job. He introduced modern design and typography but left the editorial mix mostly intact. Circulation, which had peaked around 175,000 in 1947, was 130,000 when he stepped down at the end of 1952.

To replace Bird, owner/printers Bradbury & Agnew named Malcolm Muggeridge, the 49-year-old Deputy Editor of the Daily Telegraph. He was an unlikely choice. The typical Punch editor had been a long-time staffer who had mastered the mag’s clubby ways and shared its Tory politics. Muggeridge was a self-described “incurable journalist” who had never written for Punch and claimed not to read it. Though born into the Labour Party — his father was briefly an M.P. — he became a fervent anti-Communist and Christian apologist after covering Moscow in the 1930s, yet he never lost his innate contempt for wealth, power and conventional opinion, right or left. Mainly he liked to stir things up, first in print and later on TV talk shows. With his sardonic eyebrows and lipless grin, he even looked like Mr. Punch, although he claimed to have no sense of humor — or need one: His job, he said, was to “throw a firecracker into a mausoleum.”

Muggeridge lasted only five years at Punch — the length of his starting contract, which neither side felt like renewing — but he made a century’s worth of changes. Out went whimsical anecdotes, flower-bordered poems and Richard Doyle’s 1847 cover; in came biting political cartoons, topical satire and celebrity bylines. Not everything worked, but the shake-up got Punch talked about and boosted sales, though readers eventually tired of the constant jeering. (Published numbers for Punch circulation are few and suspiciously round: Muggeridge told The New York Times in early 1956 it was “150,000 and still rising.” When he left at the end of 1957 it was “around 100,000 and decreasing at the rate of 2,000 a week,” according to industry journal Smith’s Trade News.)

“Of all Muggeridge’s devices for increasing interest . . . two stood out,” R.G.G. Price says in his History of Punch: “the Press parodies, with their typographical gaiety and literary quality, and his calculated exhibitions of what die-hard readers considered bad taste and potential readers considered a sign that Punch was not dead after all.” The bad taste was most potent in the political cartoons; Leslie Illingworth’s 1954 drawing of a listless, post-stroke Winston Churchill produced a flurry of cancellations. The parodies, Price says, sprang from Muggeridge’s “childlike love and wonder for the Press” and his habit of seeing parody as “a form of invective rather than of criticism” — though they seem subtle by current standards.

Whatever his motives, Muggeridge ran six feature-length press parodies and a handful of one-pagers. Though uncredited, most were written by J.B. Boothroyd and Richard Mallett, with art by Norman Mansbridge and Russell Brockbank. Of the longer parodies, four appeared between Spring 1954 and Spring 1955 in the oversize seasonal numbers; the later two ran in issues built around a single theme.

The Parodies:

- April 7, 1954: The New Yorker (“The N*w Y*rk*r”), 8 pages.

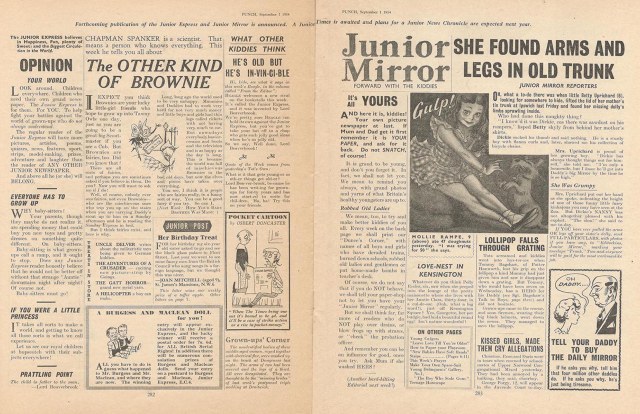

- Sept. 1, 1954: Daily Express (“Junior Express”), 1.

- Sept. 1, 1954: Daily Mirror (“Junior Mirror”), 1.

- Sept. 15, 1954: The Tatler & Bystander (“The T*tl*r & Byst*nd*r”), 4 no cover.

- Sept. 29, 1954: Radio Times (“R*d*o T*m*s”), 1, no cover.

- Oct. 13, 1954: Time (article: “Miscellany”), 0.33 [1 column], no cover.

- Dec. 15, 1954: Genre: women’s (“Her”), 6.

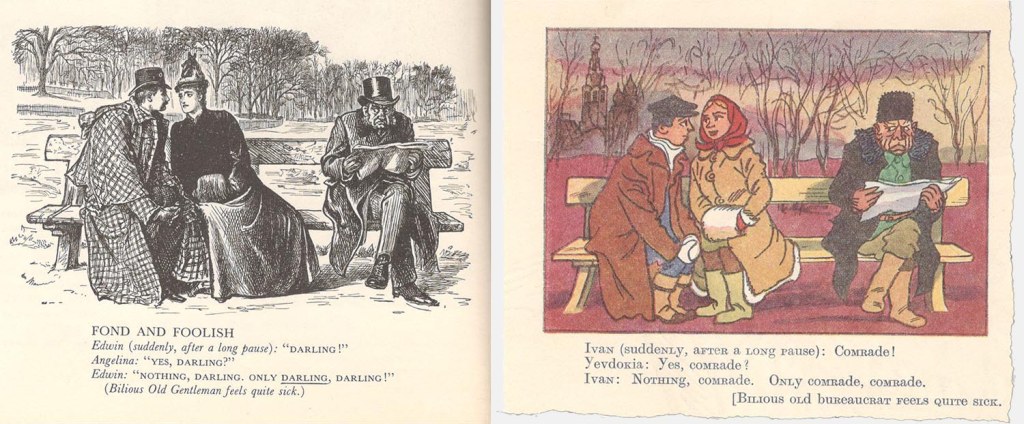

- April 6, 1955: Krokodil, 4.

- Aug. 24, 1955: Radio Times (“Tradio Times”), 6.

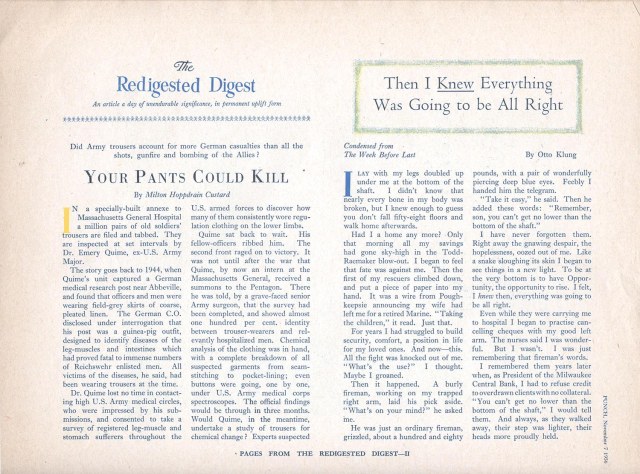

- Nov. 7, 1956: Reader’s Digest (“Redigested Digest”), 7 on 4.

The biggest and most famous was the first — an eight-page takeoff of The New Yorker in the 1954 Spring Number. Printed on slick paper with full-color front and back covers, “The N*w Y*rk*r” was delayed payback for its target’s 1934 “Paunch” (previous post) and proved just as popular on newsstands: The issue disappeared so fast Punch had to buy copies back from readers for its own files (or so I was told when I stopped by the office 20 years later). Price calls Mallett’s spoof of S.J. Perelman “the high-water mark” of Punch parodies, and it’s one of the few anywhere that rivals the original for linguistic pyrotechnics. I’m partial to the brief duet between Ogden Nash and Phyllis McGinley, and Boothroyd’s takedown of Edmund Wilson at his most Anglophobic.

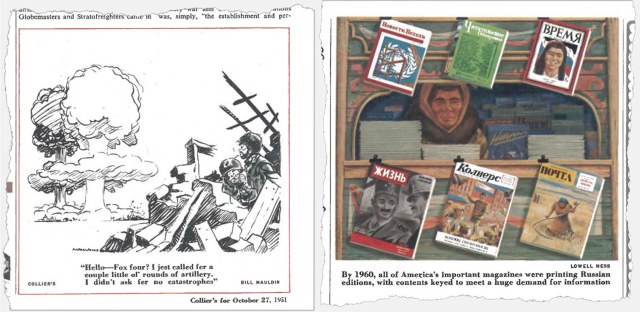

Punch reached Peak Parody in September-October 1954, beginning with contrasting kiddie versions of the staunchly conservative Daily Express, then a relatively serious broadsheet, and the pro-Labour Daily Mirror, which favored crime stories and cheesecake. “The T*tl*r & Byst*nd*r” in the 1954 Fall Number took on the leading chronicler of high society, which started as The Tatler in 1901, merged with rival Bystander in 1940 and was Tina Brown’s lauchpad to Condé Nast in the 1980s. Norman Mansbridge’s mock-photo illustrations here show a comic craftsmanship equal to anything Harvey Kurtzman’s gang was doing in Mad and Trump. It was followed by brief spoofs of esoteric BBC Radio listings and Time’s offbeat “Miscellany” column (both sitting ducks).

“Her” in the 1954 Christmas issue parodied weekly magazines for housewives, as they were then called. Bearing such titles as Woman’s Weekly (launched 1911), Woman and Home (1926), Woman’s Own (1932) and just plain Woman (1937), they were a notch or two above supermarket tabloids and several notches below slick U.S. monthlies like McCall’s. Confusingly, three months after Punch’s parody appeared, the National Magazine Company launched a new title aimed at “young, gay, elegant” postwar women who wanted more from life than the domestic pieties satirized in “Her.” Its name: She. Coincidence or Fleet Street in-joke?

The parody of Russian humor weekly Krokodil in the 1955 Spring Number flayed two of Muggeridge’s favorite targets: Soviet Communism and Punch itself (which he more than once called “an allegedly humorous publication”). While the written pieces play up the iron teeth behind Krokodil’s state-sanctioned grin, the cartoons transfer some of Punch’s most famous gags from the 19th Century to contemporary Russia but leave them otherwise un-updated. Trust Muggeridge to display the family heirlooms in a deliberately unflattering setting.

The coming of commercial television inspired a second takeoff of the BBC’s program guide, Radio Times (founded 1923 as Radio Times and never retitled). The page of fake radio listings the year before had been an almost affectionate sendup of the wireless division’s fondness for the obscure and undramatic. “Tradio Times” — as in, “being in trade” (sniff) — is an all-out and rather snobbish attack on the threat to public taste and intelligence posed by for-profit TV, which debuted in London the week the parody appeared. The authors try to imagine the worst in their “journal of the I.T.A.” — the Independent Television Authority — but reality has long since outrun satire: “Tradio’s” tropes include kids’ shows that are basically one long commercial, programs entirely about shopping, “film sequences of kittens at play” and, most popular of all, a reality series about a clan of shallow materialists called “The Trump Family.” I didn’t make that up.

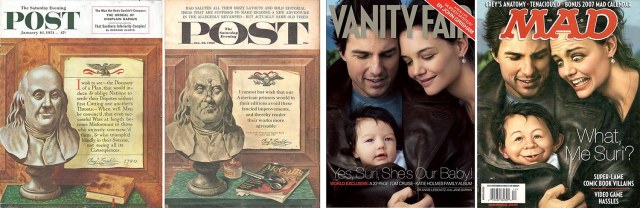

More than a year went by before “Redigested Digest” appeared in November 1956, and there were no press parodies at all in 1957, Muggeridge’s last year. At least the series ended on high note. For my money, “Redigested Digest” is Punch’s best press parody ever, and the best anywhere at catching the contradictory soul of Reader’s Digest: its All-American universalism, its fondness for “characters” and even greater fondness for conformity, its fascination with new inventions and suspicion of new ideas. Punch’s “Digest” is as artfully crafted as “The N*w Y*rk*er” and much more incisive, though not nearly as famous. To help remedy that, I’ve posted all six (on three) pages here.

The “Digest’s” only flaw was bad timing: It was the centerpiece of a long-planned issue about the U.S. scheduled to coincide with the 1956 Presidential election, but Eisenhower’s easy win ended up being overshadowed by the Soviet invasion of Hungary and the climax of the Suez Canal crisis. The issue hit the stands just days after the U.S. forced the U.K., France and Israel to end their attack on Egypt, which demolished Britain’s remaining claims to be a Great Power and caused a brief but steep drop in Anglo-American amity. Not the best time to market 30 pages of mostly good-natured kidding about Uncle Sam’s worldwide reach.

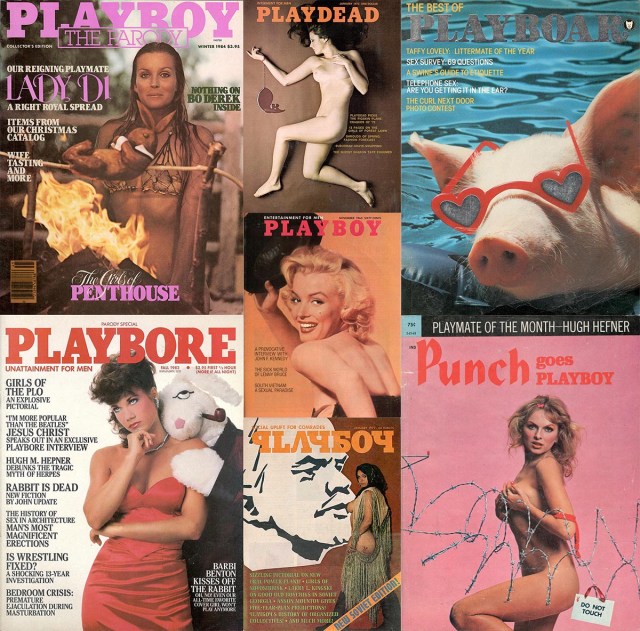

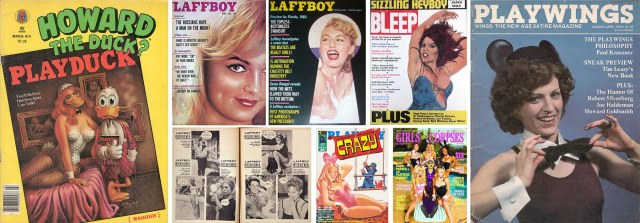

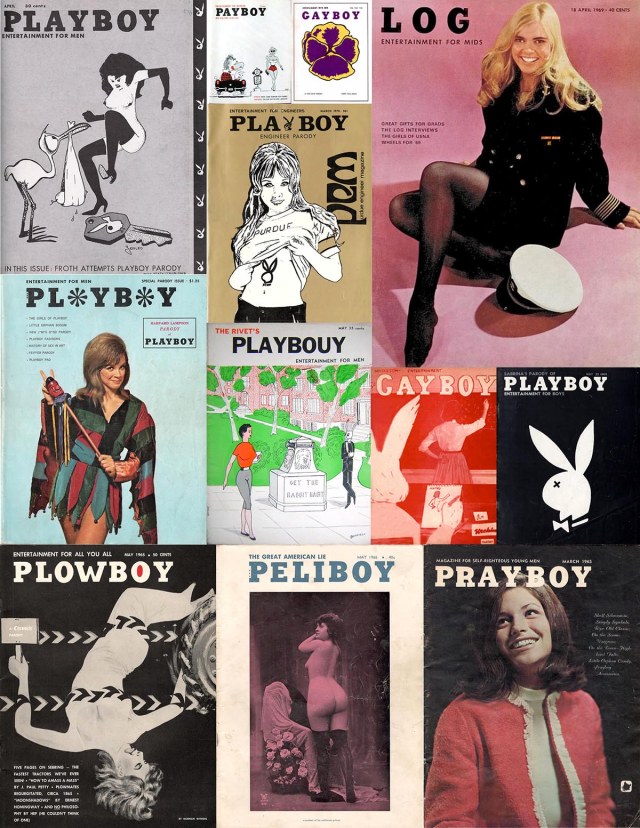

None of the standard sources explain why Punch basically abandoned press parodies after the mid-50s, but the drought continued under Bernard Hollowood, editor from 1958 to 1968. It only ended in 1971, when Hollowood’s successor William Davis devoted most of an issue to parodying Playboy. Like “The N*w Y*rk*r” before it, “Punch Goes Playboy” sold out and inspired a run of similar features. But that’s a subject for another post. — VCR.