The first issue of National Lampoon, dated April, hit newsstands on March 19, 1970. It did not hit my P.O. box in Davidson, North Carolina, however, despite the Occupant being a charter subscriber at the bullseye of the target demo: White, Male, Twentyish, Collegiate, Too Old for Mad but still reading it. Thwarted by mail, I bummed a ride to the nearest newsstand in Charlotte and bought what turned out to be a famously underwhelming debut.

“The April issue seems to be made up almost completely of dull material rejected from the three old [Harvard Lampoon] magazine parodies,” the Crimson wrote, citing “Pl*yb*y” (1966), “Life” (1968) and “Time” (1969). “The National Lampoon will be chalked up as a business failure unless the overall quality of the publication improves soon.” So it seemed: The inaugural “Sexy Cover Issue” sold 225,000 of 500,000 copies printed; the May issue, devoted to “Greed,” sold 120,000.

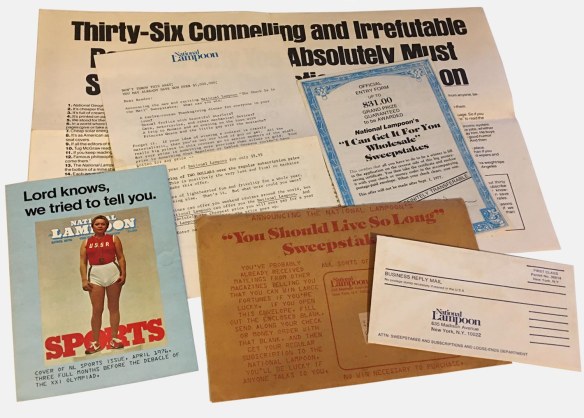

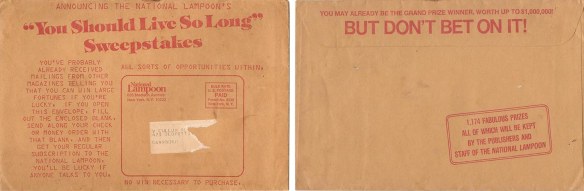

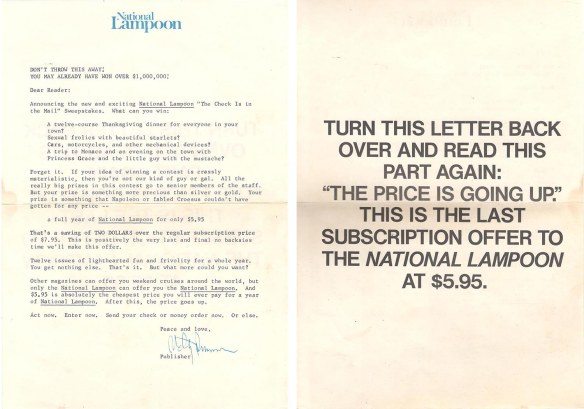

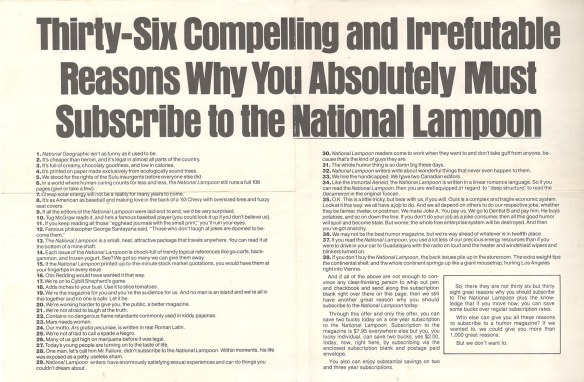

Both quality and sales picked up fast, but the Circulation Dept. never became a model of efficiency. After years of seeing copies in stores first, I let my subscription lapse and started buying retail. Several addresses later, most likely in the summer of 1977, I received this item in the mail. It’s not quite a magazine parody, but it does make fun of the industry’s most famous marketing gimmick. To my knowledge, it’s never been posted — or even mentioned — online, so as a service to posterity here’s National Lampoon’s “You Should Live So Long” Sweepstakes (fake) and subscription pitch (real).

It’s modeled on the fat envelopes Publishers Clearing House and others used to send out by tens of millions, promising cash, cars and homes to random lucky-number holders. Finding one’s number and correctly filling out the entry form could involve hours of sticker-peeling, card-scratching and stamp-pasting, all crafted to jolly Occupant or Current Resident into buying short-term magazine subscriptions at steep discounts. Contest rules and federal law might swear no purchase was necessary, but lots of folks were naive or cynical enough to think signing up for six months of Knitting World couldn’t hurt. The final nudge was the separate envelopes for entries with and without orders, the latter often stamped “NO” in huge block letters.

Contestants were right to suspect something fishy: One lawsuit in the 1990s discovered thousands of never-opened “NO” envelopes in an unused office. State attorneys general eventually put most of the sweeps out of business, but it was the magazines that suffered most while they flourished. Back in 1893, publisher Frank Munsey cut the cover price of his self-titled monthly from a quarter to a dime. Sales of Munsey’s went from 40,000 copies to 500,000 in six months and pioneered a new business model: Price the magazine low to draw a mass audience and sell its eyeballs to advertisers at so much per thousand. When TV took off in the ’50s, publishers began hiring outfits like PCH (founded 1953) and American Family Media (1977-1998) to make sure the promised eyeballs were present, even it if meant giving copies away. The salesmen kept most of the money, and the mags got thousands of low-margin, short-term subscribers who seldom renewed. Publishers came to hate this arrangement but couldn’t afford to quit playing the numbers game unilaterally.

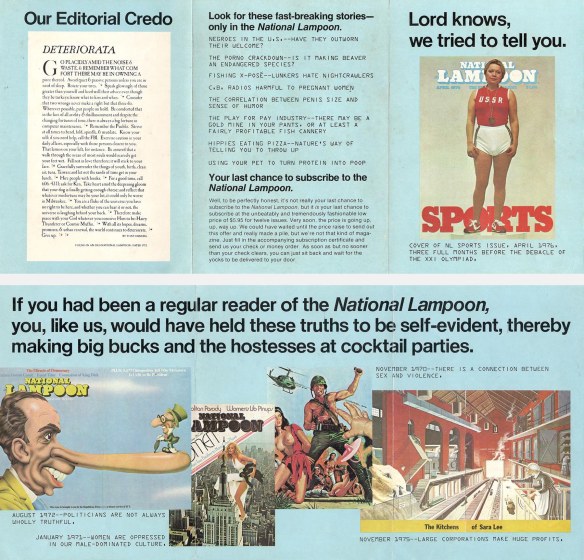

National Lampoon mocked the sweepstakes ballyhoo mainly by being honest about the odds: ‘You May Already Be The Grand Prize Winner, Worth Up To $1,000,000! BUT DON’T BET ON IT!” warns one side of the outer envelope; “No Win Necessary To Purchase,” says the other. The mailing isn’t postmarked, but internal evidence sets it between the 1976 Montreal Olympics and the September 1, 1977, “entry” deadline. There’s no direct evidence it was written by the NL’s editors — who in 1977 included Tony Hendra, Sean Kelly, P.J. O’Rourke and Gerald Sussman — but it’s hard to believe the marketing department made the decision to list “Negroes In the U.S.: Have They Outworn Their Welcome?” among the mag’s “fast-breaking stories.” (The same crack was used on the front of the Sunday Newspaper Parody in 1978, though no such story appeared inside.)

The line between editorial and merchandising was blurry from the start at NatLamp: The Harvard founders appeared in subscription ads (“Little Doug Kenney Will Go to Bed Hungry Tonight”), as did later editor P.J. O’Rourke and publisher Matty Simmons, whose “Authorized Signature” is the only name attached. The one trustworthy statement anywhere appears on the back of the return envelope: “Have you enclosed your check and subscription blank?”

Publishers Clearing House is still around, mostly online; it’s better known today for its Prize Patrol ads at Superbowl time than for its mailings, and magazines are just one product among many. Especially since 9/11, publishers have shifted more of the real cost of their wares onto readers: In 2019, the average subscriber to People paid over $90 for a year (54 issues), or about $1.70 a copy. Still better than the $5.99 cover price, but a long way from four easy monthly payments of $1.79. — VCR

Of all the magazine parodies I’ve heard of but never seen, 1963’s anonymous “Newsweek International Edition” is the most puzzling. Calling it “a vicious piece of propaganda,” the real Newsweek for January 13, 1964, laid out the few facts available: “Purporting to be the Nov. 18, 1963, issue of Newsweek with a cover picture of Sen. Barry Goldwater, the hate pamphlet is a mishmash of doctored photographs and inflammatory captions in French and English, apparently designed to foment race hatred and anti-American sentiment. A number of copies were mailed from Europe, but efforts to track down the publishers and distributors have been unsuccessful.”

Of all the magazine parodies I’ve heard of but never seen, 1963’s anonymous “Newsweek International Edition” is the most puzzling. Calling it “a vicious piece of propaganda,” the real Newsweek for January 13, 1964, laid out the few facts available: “Purporting to be the Nov. 18, 1963, issue of Newsweek with a cover picture of Sen. Barry Goldwater, the hate pamphlet is a mishmash of doctored photographs and inflammatory captions in French and English, apparently designed to foment race hatred and anti-American sentiment. A number of copies were mailed from Europe, but efforts to track down the publishers and distributors have been unsuccessful.” I’m more confident that whoever created this “Newsweek” either hadn’t seen the original recently or assumed potential readers hadn’t. The cover resembles a typical Newsweek from 1949 or ’50, when its lopsided-red-border-and-square-photo format was new and not yet plastered with boxes and banners. Newsweek began stripping away this effluvia in 1961 and by mid-’62 was running full-bleed covers topped only by its underlined name, as in the real November 18, 1963, issue shown here. Whatever his(?) talents as a propagandist, the creator of “Newsweek” was no great shakes as a parodist. — VCR

I’m more confident that whoever created this “Newsweek” either hadn’t seen the original recently or assumed potential readers hadn’t. The cover resembles a typical Newsweek from 1949 or ’50, when its lopsided-red-border-and-square-photo format was new and not yet plastered with boxes and banners. Newsweek began stripping away this effluvia in 1961 and by mid-’62 was running full-bleed covers topped only by its underlined name, as in the real November 18, 1963, issue shown here. Whatever his(?) talents as a propagandist, the creator of “Newsweek” was no great shakes as a parodist. — VCR No sooner do I launch this blog than a group of mostly web-based humorists go and release a full-length parody of The New Yorker called “The Neu Jorker.” You can read it

No sooner do I launch this blog than a group of mostly web-based humorists go and release a full-length parody of The New Yorker called “The Neu Jorker.” You can read it