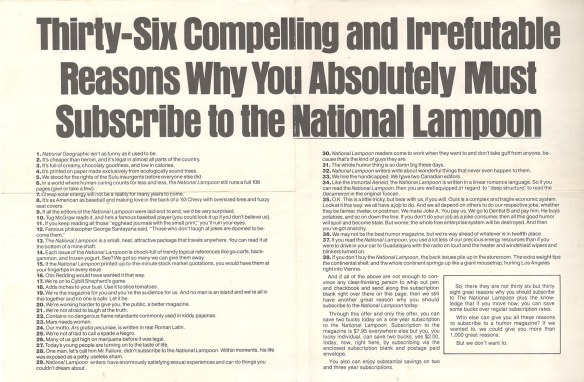

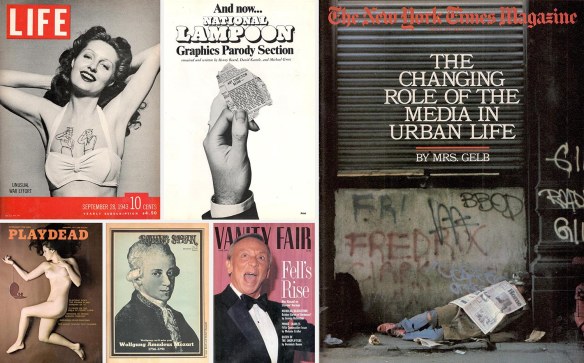

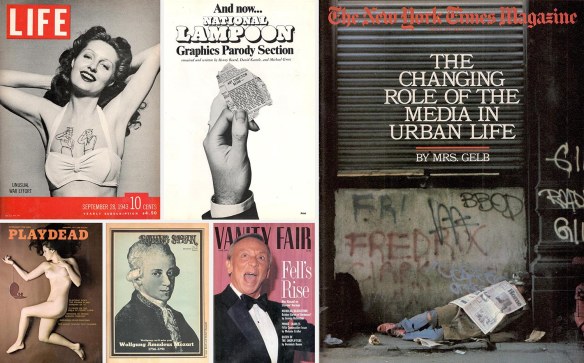

Clockwise from Mozart: Early parodies of Rolling Stone (1970), Playboy (1973) and Life (1973), a special for Print (1974); late parodies of the Times Magazine (1984) and Vanity Fair (1990).

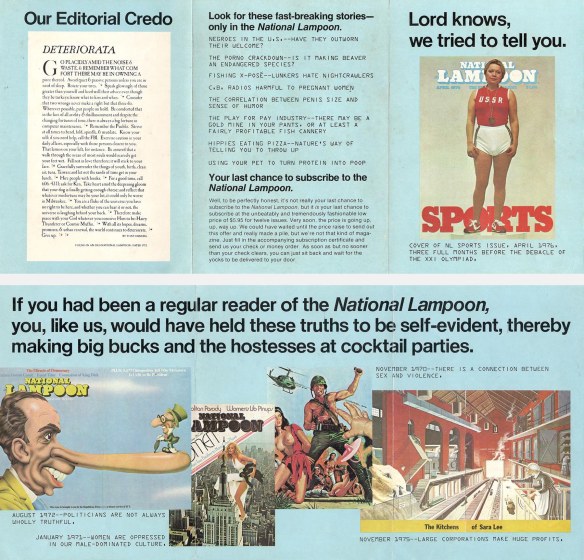

This week’s debut on Netflix of another movie about the early years of National Lampoon — not a documentary this time, a biopic of Doug Kenny — provides all the excuse I need to catalog its magazine and newspaper parodies. Founders Kenney, Henry Beard and Rob Hoffman honed their chops aping Playboy, Life and Time at the Harvard Lampoon , so it’s no surprise magazine parodies were highlights of NatLamp’s Golden Age (roughly 1971-75) and bright spots in the silver-plated years that followed (roughly 1976-84; the mag’s post-1984 content is mostly lead).

The contract licensing the “Lampoon” name to Twenty-First Century Communications explicitly barred the national version from milking Harvard’s cash cow. The closest National Lampoon ever came to producing a full-length, stand-alone magazine parody was the November 1977 “Lifestyles” issue, which aped New York from cover lines to crossword puzzle without quite admitting what it was up to. Fortunately, the contract said nothing about parodies of generic high-school yearbooks and small-city Sunday papers, leaving the door open for NatLamp’s masterpieces.

Top: NL’s “Lifestyles” issue (Nov. 1977); bottom: New York pages from 1976-77.

National Lampoon’s fake publications fall into four types: inventions, genre spoofs, mutations and plain ol’ parodies. Like Mad’s fake mags for protesters, schoolteachers and what-have-you, the inventions were vessels for satire aimed at some other target. And as with the earlier Mad index, they’re not listed here. Genre spoofs imitated types of publications — often fan magazines or gossip tabloids — without cloning any one title. Examples include “Real Balls Adventure” for men (April 1971) and the inflight magazine “Stampede” (April 1974). I suspect some items I’ve put in this category have specific models I’m not familiar with, and I’d welcome additional info.

The mutations spoofed specific titles but tinkered with their DNA, making My Weekly Reader a scandal sheet (Sept. 1971) or switching Hot Rod’s focus from gearheads to tree-huggers (“Warm Rod,” April 1975). A few were relatively straight counterfactuals: e.g., the parodies of Look, Jet and the Village Voice in the JFK Fifth Inaugural issue (Jan. 1977). Others put familiar mags in Bizarro worlds where plants crave porn (“Seed,” Aug. 1974) and military service is a fashion statement (“Guerre,” Sept. 1973). This approach reached perfection in “Playdead” ( Jan. 1973), which exposed the airbrushed unreality of Playboy simply by redirecting its covetous ogle from skin to bones.

Four kinds of fakes: Invented, genre, mutated, and plain ol’ parody.

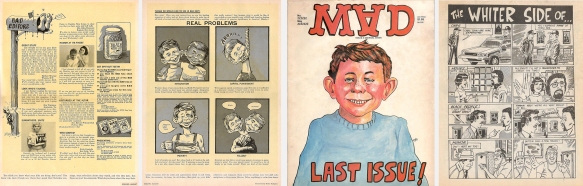

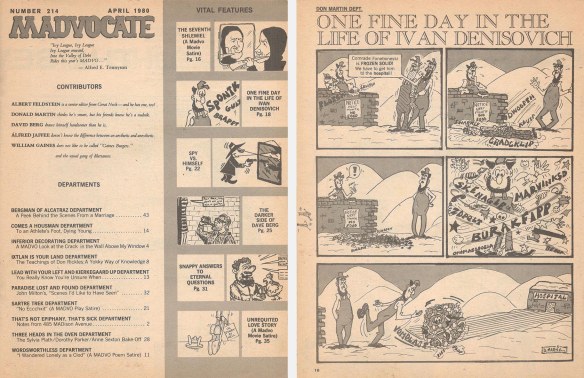

The plain ol’ parodies dispensed with what-ifs and tackled publications just as they were. This group includes many NatLamp’s classics, including “Mad” (Oct. 1971), the 1943 “Life” (Sept. 1973) and what I consider its last first-rate feature of any kind, a 19-page sendup of The New York Times Magazine in June 1984. Also included are a few items that aren’t strictly parodies but capture the essence of a publication, such as “Ron Hague’s Year of Rejected New Yorker Covers” (Dec. 1983) and “National Lampoon’s 1974 New Year’s Resolutions” (Jan. 1975).

This list is divided into three unequal parts: parodies in regular issues, those in books and specials containing new material, and those in non-NL publications. (The last section contains only one item, but it’s a hoot if you’re into graphic design.) Each entry in Section 1 begins with the name of the publication being parodied, in italics; followed by the fake title or article name, in parentheses; the NatLamp issue date; and the page count, in brackets.

A phrase like “5 pages on 3” means each magazine page contained two or more digest-size parody pages; the word “broadsheet” describes a few newspaper parodies that folded out to 17″ by 22″. Parodies of old magazines have their cover dates noted inside the parentheses: e.g., “Popular Workbench” for Aug. 1938.

A version of this list in alphabetical instead of chronological order will appear in my very next post. —VCR

Section 1: Parodies in National Lampoon Magazine, 1970-98:

1970

Avant Garde (“Avant Gauche” ad: “Rockwall’s Erotic Engravings”), April 1970 [3]

Playboy (foldout: “Liberated Front” + “Party Jokes”), April 1970 [6]

Genre: confession (“True Finance”), May 1970 [4]

Wall Street Journal (“The Gall Street Journal”), May 1970 [2 broadsheet]

Harper’s Bazaar (“Bizarre”), June 1970 [5]

Life [pictue mag] (article: “Our Threatened Nazis”), June 1970 [2]

Genre: underground newspaper (“The Daily Roach Holder”), August 1970 [6]

Genre: movies (“Screen Slime”), Sept. 1970 [10]

Variety (“Varietsky” front page), Sept. 1970 [1]

Variety (“Varietsky” front page), Sept. 1970 [1]

1971

Cosmopolitan (“Cosmopolatin”), Jan. 1971 [15]

Rolling Stone (“Rolling Stein,” Dec. 9, 1791), Feb. 1971 [3]

TV Guide (“The New York Review of TV”), March 1971 [5 pages on 3]

Genre: men’s (“Real Balls Adventure”), April 1971 [11)

Life [humor mag] (“National Lampoon,” May 1906), May 1971 [7]

New York Times (“The New York World”), May 1971 [2 broadsheet]

My Weekly Reader (“My Weekly Reader: The Children’s Tabloid”), Sept. 1971 [4]

Mad (“Mad”), Oct. 1971 [15]

Esquire (article: “The Incredible Shrinking Magazine”), Nov. 1971 [3]

1972

The Whole Earth Catalog (“The Last, Really, No Shit, Really, the Last Supplement to the Whole Earth Catalog”), Jan. 1972 [7]

Screw (“Third Base: The Dating Newspaper,” April 1956), April 1972 [8]

Playboy (article: “Gamma Hutch: The Playboy Fallout Shelter,” Dec. 1959), April 1972 [4]

Genre: true story (“True Politics”), Aug. 1972 [10]

National Geographic (“National Geographic”), Sept. 1972 [3]

New York Times (“The New York Times”), Oct. 1972 [1 page on 2]

1973

Playboy (“Playdead”), Jan. 1973 [14]

Screw (“Piddle: The Adult Publication for Children”), Feb. 1973 [8]

National Enquirer (“National Inspirer”), March 1973 [8]

Ebony (“Ivory”), April 1973 [7]

Genre: guns (“Gun Lust”), June 1973 [11]

Genre: men’s (“Knuckle: A Real Man’s Magazine”), June 1973 [5]

Popular Mechanics (“Popular Workbench,” Aug. 1938), July 1973 [14]

Psychology Today (“Psychology Ptoday”), Aug. 1973 [15]

Genre: fashion (“Guerre: The New Magazine for the New Army”), Sept. 1973 [7]

Life (“Life,” Sept. 28, 1943), Sept. 1973 [13]

Reader’s Digest (article: “Martial Mirth”), Sept. 1973 [1]

Oui (“Peut-etre” article: “Taffy”), Oct. 1973 [4]

Sports Illustrated (“Sports Illustrated”), Nov. 1973 [13]

Tiger Beat (“Poon Beat”), Dec. 1973 [10]

1974

Penthouse (“Pethouse”), Jan. 1974 [9]

Popular Science (“Popular Evolution”), Jan. 1974 [11]

National Lampoon (“National Lampoof”), Feb. 1974 [11]

U.S. News & World Report (“Stupid News & World Report”), March 1974 [7]

Genre: inflight (“Stampede: Prairie Central/Panhandle Airlines Magazine”), April 1974 [8]

Reader’s Digest (“Digester’s Reader” front & back covers only), June 1974 [1]

Weight Watchers (“Weighty Waddlers”), June 1974 [7]

Genre: guns (“Guns & Sandwiches”), July 1974 [6]

Family Circle (“Famine Circle”), July 1974 [8]

Screw (“Seed”), Aug. 1974 [8]

Genre: pulps (“Unexciting Stories,” undated but 1930s), Sept. 1974 [4+]

Ladies’ Home Journal (“Old Ladies’ Home Journal”), Sept. 1974 [8]

National Midnight (“Almost Midnight”), Sept. 1974 [4]

Playboy (ad: What Sort of Man Reads Pl*yb*y?”), Oct. 1974 [1]

Boys’ Life (“Boys’ Real Life”), Oct. 1974 [10]

Awake! (“Wise Up!”), Dec. 1974 [3 half-pages]

1975

National Lampoon (article: “NL’s 1974 New Year’s Resolutions”), Jan. 1975 [5]

Genre: homemaker (“Negligent Mother”), Jan. 1975 [6]

Modern Bride (“American Bride”), Feb. 1975 [10)

Modern Bride (“American Bride”), Feb. 1975 [10)

The New Yorker (“The New Y*rker”), March 1975 [13]

Time (article: “Partly Sane, Raspberries, and Time”), March 1975 [3]

Hot Rod (“Warm Rod”), April 1975 [7]

JAMA: Journal of the American Medical Association (“COMA: Circular of the Organization of Medical Associations”), May 1975 [8]

National Star (“National Sore”), May 1975 [4]

Genre: boys’ magazines (“Cap’n Jasper’s Boy O Boy,” May 1935), June 1975 [8]

Genre: show-biz trade paper (“Hollywood Briefs”), July 1975 [4]

After Dark (article: “Glitter Bums”), July 1975 [3]

Harvard Lampoon (article: “The Ten Worst Movies of All Time”), July 1975 [1]

Genre: true crime (“Citizen’s Arrest”), Aug. 1975 [7]

Esquire (“Exsquire”), Sept. 1975 [12]

Genre: college newpapers (“The Daily Klaxon”), Sept. 1975 [4]

Penthouse (article: “The Resister’s Revenge”), Sept. 1975 [6]

Genre: gossip (“Myth & Legend Mirror” for Oct. IV B.C.), Oct. 1975 [5]

Fortune (“Lucre”), Dec. 1975 [12]

Moneysworth (two subscription ads for “Nickleknows”), Dec. 1975 [1+1]

1976

New Times (“Nu? Times” cover only), Jan. 1976 [1]

New York Review of Books (“The New York Review of Us”), Jan. 1976 [8]

ARTnews (“ARTynews”), Feb. 1976 [13]

Genre: art studies (“Modes d’Art Magazine” for June 1926), Feb. 1976 [6]

The Sporting News (“The Sportbiz News”), April 1976 [6]

Genre: fan & gossip (“Silver Jock: The Demi-Decadent Sports Magazine), April 1976 [7]

Cahiers du Cinema (“Cahiers du TV”), May 1976 [4]

The Times of India (“The Times of Indira”), May 1976 [3]

The Canadian Magazine (“The Canadian Weakly,” June 8, 1969), June 1976 [6]

Hustler (“Gobbler”), Aug. 1976 [5]

Newsweek (cover + article: “Townville, Iowa”), Nov. 1976 [2]

People (“Objects”), Dec. 1976 [5, no cover]

1977

The Kiplinger Washington Letter (“The Kremlinger Moscow Letter”), Jan. 1977 [2]

Scientific American (“Scienterrific American”), Jan. 1977 [10]

Look (“Kennedy”), Feb. 1977 [11]

Jet (“Tar”), Feb. 1977 [6, digest-size]

The Village Voice (“The Global Village Voice”), Feb. 1977 [8]

TV Guide (“TV”), Apr. 1977 [16, digest-size]

Better Homes and Gardens (“Better Homes and Closets”), May 1977 [11]

Money Matters (“Young Money Matters”), June 1977 [4]

Penthouse (“Repenthouse”), July 1977 [5]

High Times (“Wasted Times”), Aug. 1977 [7]

Amazing Stories (“Amusing Stories” for Oct. 1926), Sept. 1977 [3]

Mad (article: “You Know You’re Grown Up When…”), Sept. 1977 [2]

Genre: fan & gossip (“Mersey Moptop Faverave Fabgearbeat” for Oct. 1964), Oct. 1977 [8]

The New York Times (“The New York Time”), Oct. 1977 [front page on 2]

New York (“Lifestyles”), Nov. 1977 [42 + front cover]

Time (“Xmas Time”), Dec. 1977 [5]

1978

National Review (“National Socialist Review”), Feb. 1978 [8]

Outside (“OutSSide” subscription ad), Feb. 1978 [3]

Reader’s Digest (article: “Rumpus Room Rib-Ticklers”), May 1978 [2]

Seventeen (“Savvyteen”), Aug. 1978 [8]

GQ (“RQ: Regular Guy Quarterly”), Sept. 1978 [4]

Variety (“Movies”), Oct. 1978 [4]

1979

Life (“Lite”), April 1979 [8]

1980

Genre: UFOs (“Real Business Jet”), March 1980 [5]

Genre: UFOs (“Real Business Jet”), March 1980 [5]

Genre: men’s (“Real-Life Adventure”), June 1980 [4]

The New Yorker (article: “Coming Into the River,” by “John McPhoo”), June 1980 [6]

National Enquirer (“The Washington Enquirer”), Aug. 1980 [4]

1981

People (article: “Douglas Waterman Caps a Big Year”), May 1981 [4]

New York Times Book Review (article: “Would You Like Something to Read?”), Aug. 1981 [2+]

Time (Special Section: “Let’s Get It Up, America”), Aug. 1981 [27]

New York Times Magazine (article: “Talking Out Loud: College Slang of the Eighties,” by “William Zircon”), Sept. 1981 [1+]

Genre: TV listings (“American Home Movie Box Program Guide”), Oct. 1981 [4]

The Hollywood Reporter (“The Hollywood Informer”), Oct. 1981 [5]

Esquire (“Esquare”), Dec. 1981 [13]

Interview (“Interluude”), Dec. 1981 [11]

Wet (“Moist”), Dec. 1981 [9]

1982

Heavy Metal (“Semi Mental” art portfolio), Jan. 1982 [6]

Cinefantastic (“Cinefantasterrifique”), Jan. 1982 [5]

Cinefantastic (“Cinefantasterrifique”), Jan. 1982 [5]

Jack and Jill (“Jack and Jill St. John”), Feb. 1982 [5]

Playboy (article: “Parents of the Girls of the Eastwest Conference”), Feb. 1982 [2]

Playboy (article: “The Playboy Advisor”), Feb. 1982 [1]

Gourmet (“Goormay”), March 1982 [9]

Road & Track (“Food & Track”), March 1982 [5]

Genre: fan & gossip mags (“Mitch Springer: A Loving Tribute”), April 1982 [5]

Self (“Self-Destruct”), April 1982 [5]

Genre: visitor guides (“Why Leave This Room?”) Aug. 1982 [5]

New York Times Magazine (article: “Talking Out Loud: The Customers Always Write,” by “William Zircon”), Aug. 1982 [1+]

National Enquirer (“National Sexloid”), Sept. 1982 [5]

National Lampoon (article: “False Facts”), Sept. 1982 [1]

Time (article: Henry Kissenger’s “Years of Arousal”), Sept. 1982 [6]

Rolling Stone (“Rolling Tombstone”), Nov. 1982 [9]

1983

The Dial (“hy-Art: The Magazine of the Precious Broadcasting System”), Jan. 1983 [7]

Travel & Leisure (“Postage & Handling”), Feb. 1983 [7]

The Atlantic (“The Hotlantic”), April 1983 [9]

National Geographic (“National Southpacific”, May 1983 [13]

Playboy (article: “Dear Playmates”), June 1983 [1]

Genre: alumni (“Skidmark: The Alumni Magazine of Skidmark College”), Sept. 1983 [11]

New York (“Jo’burg”), Sept. 1983 [9]

Working Woman (“Working Girl”), Nov. 1983 [11]

The New Yorker (article: “Ron Hauge’s Year of Rejected New Yorker Covers”), Dec. 1983 [4]

1984

Time (“Time”), Jan. 1984 [35]

Easyriders (“Equalriders”), March 1984 [11]

New York Times Magazine (“The New York Times Magazine”), June 1984 [19]

The New Yorker (“The Hymie Towner” cover only), June 1984 [1]

People (“PLO” article: “Nor More Mr. Bad Guy For Yassir Arafat”), July 1984 [4]

Genre: TV listings (“Unofficial 1984 Olympic TV Watcher’s Guide”), Aug. 1984 [16 digest-size]

Genre: fitness (“Muscle Mind”), Sept. 1984 [7]

1985

Forum (“Whorum”), Jan. 1985 [8]

Seventeen (“Deadteen”), July 1985 [7]

Easyriders (“Easywriters”), Sept. 1985 [8]

Multiple titles (article: “The Hot New Lineup for 1986 from Condom-Nasty Publications,” with covers of STD-focused versions of Harper’s Bazaar, Reader’s Digest and New Age Journal), Sept. 1985 [2].

Rolling Stone (“Rollin’ Home” for Itinerant Bluesmen), Oct. 1985 [6]

Multiple titles (article: “The Real Story of Rock ‘n’ Roll,” told in fake clips from the New York Post, People, Jet, etc.), Oct. 1985 [7].

Playboy (“Slayboy”), Dec. 1985 [8]

1986

Fortune (“Misfortune”), Feb. 1986 [13]

National Lampoon (“National Tampoon”), March 1986 [6]

Playboy (article: “Feminist Party Jokes”), March 1986 [1]

Sports Illustrated (“Sports Hallucinated”), May 1986 [7]

Playboy (article: “Interview: Steven Spielberg”), Aug. 1986 [3+]

Genre: tabloid (“Stranger Than Fact”), Nov. 1986 [7]

1987

Genre: fitness (“Peppy: The High-Potency Magazine of Fitness and Health”), Jan. 1987 [12]

1988

Playboy (“Playbyte”), Feb. 1988 [10]

Sporting News (“The Sporting Muse”), Oct. 1988 [10]

1989

Rolling Stone (“Rolling Stone”), Feb. 1989 [7]

Playboy (article: “Girls of the Community Colleges”), Oct. 1989 [4]

Martha Stewart Entertaining (“Martha Stewart’s Entertaining the K-Mart Way”), Dec. 1989 [3]

1990-1998

Rollling Stone (“Perception/Reality” ad), Feb. 1990

Vanity Fair (“Vanity Fair”), June 1990 [10]

Genre: movies (“Big Screen”), June 1991 [36]

Rolling Stone (article: “Have War, Will Travel,” by “P.J. O’Drunke”), Aug. 1991 [2]

Muscle & Fitness (“Muscle & Fatness”), March 1994 [9]

Guns & Ammo (“Liquor & Ammo”), Aug. 1994 [10]

Reader’s Digest (“Reader Digest”), Jan.-Feb. 1995 [10]

Genre: golf (“Duffer’s Digest”), 1996 [9]

National Enquirer (“Roman Eqvirer”), 1996 [4]

Inc. (“stInc.”), 1998 [13]

Section 2: Parodies in Special Editions and Books, 1974-2006:

In the 1964 High School Yearbook Parody, special edition, Summer 1974:

Genre: high school newspaper (“The Prism” for May 11, 1964) [8]

Genre: high school literary magazine (“Leaf & Squib” for Spring 1964) [14]

In NL’s 199th Birthday Book, special edition, 1975:

Genre: college humor (“The Spitoon,” for 1877) [2]

Kiplinger Washington Letter (“The Hamilton Philadelphia Letter,” Sept. 18, 1787) [2]

Popular Mechanics (“Tomorrow’s Future Homebody” for June 1946) [3]

In NL’s Sunday Newspaper Parody, special edition, Feb. 1978:

Genre: newspaper (“The Dacron-Republican-Democrat”) [104, in 8 sections]

Genre: newspaper magazine section (“Sunday Week”) [16]

Parade (“Pomade”) [16]

In NL Magazine Rack (New York: National Lampoon Press, 2006):

Consumer Reports (“Consumed Reports”), from nationallampoon.com, June 2004 [4]

The Hollywood Reporter (“The Hollywood Retorter”), limited distribution, Dec. 2002 [16]

Men’s Health (“Man’s Health”), from nationallampoon.com, June 2002 [4]

TV Guide (“Al-Jazeera TV Guide”), from nationallampoon.com, Nov. 2004 [4]

Section 3: Parodies in Non-National Lampoon Publications:

Print (“National Lampoon Graphics Parody Section”), in Print, July-Aug. 1974 [8 + cover]