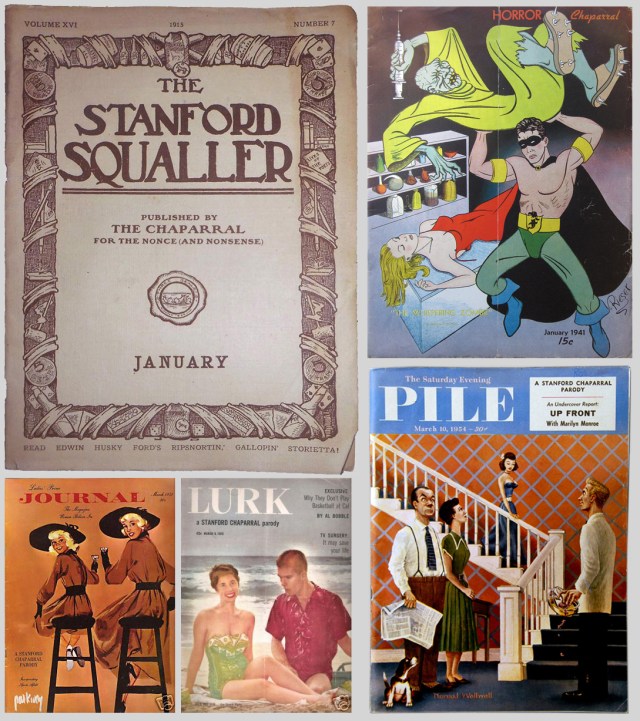

When is a parody not a parody? When it’s a straight-faced, money-grubbing imitation, according to the courts. Lawsuits over parodies of copyrighted works are rare and their outcomes unpredictable, but two things any accused parodist better be able to show are (1) that no reasonable person could mistake the parody for the Real Thing, and (2) that the parody hasn’t cut into the Real Thing’s sales. The easiest way to avoid this fix is to make the parody as unlike its target as possible, but that rather defeats the purpose. So parodists find themselves sweating to duplicate the look and tone and subject matter of a particular publication, while at the same time making clear to the even densest readers that what they’re holding isn’t that publication. It’s a rare and delicate art, and it’s how parodists justify their massive paychecks (joke).

Occasionally, however, some enterprising pirate cuts through the niceties and kidnaps a format in broad daylight, strictly for profit. In 1972, a businessman named Ronald Fenton launched a men’s magazine called Gallery, with lawyer F. Lee Bailey as figurehead publisher. “Fenton not only copied the Playboy formula — he copied the magazine line for line, picture for picture, party joke for party joke,” Aaron Latham wrote in New York soon after the first issue appeared. “The only thing he changed was the name” — and even there he made sure to imitate Playboy’s distinctive logo. Time cracked that Gallery was “perhaps meant to be mistaken for [Playboy] on newsstands by the nearsighted,” and said Hugh Hefner’s lawyers were inspecting the first issue for possible copyright infringement; even Bailey thought the mag was too obviously a Playboy clone. “Gallery’s next issue is to be partly redesigned,” Time noted, “but Fenton is unworried. ‘All magazines,’ he says blandly, ‘have similarities.'”

Hefner chose to ignore Gallery, which soon shed its Playboyish pretensions and became just another skin mag. Giant Reader’s Digest (circulation 17 million) wasn’t so sanguine in 1985, when a small Colorado-based monthly named Conservative Digest (circulation 15,000) shrank its page size and began printing its table of contents on the cover. Though the contents were back inside after two issues, Reader’s Digest sued for copyright and trademark infringement anyway and asked for $1.2 million. In June 1986 U.S. District Court Judge Gerhard Gesell found that Conservative Digest had “copied Reader’s Digest’s trade dress in a manner which created a likelihood of confusion,” but awarded the larger magazine only $500 for trademark infringement and nothing for actual damages. Gesell reproved the big Digest for “relentlessly” pursuing the small one, but he saved his sharpest zinger for Conservative Digest editor Scott Stanley Jr.: “Mr. Stanley … testified that he did not copy Reader’s Digest‘s front cover but by chance happened to achieve complete identity while casually developing his own ideas for a new cover using a design computer,” the judge wrote in a footnote. “This testimony, reminiscent of Greek mythology recording the birth of Athena who sprang full-grown from the head of Zeus, is not worthy of belief and is rejected.”

For truly blatant appropriation, it’s best to be outside U.S. jurisdiction altogether. Every newsmagazine since 1923 has lifted its basic format from Time, but Britain’s Cavalcade took everything else, too — from the cheeky tone and convoluted syntax to the shape of the dingbats separating short news items. Cavalcade would have been the first British newsmagazine, but editor Alan Campbell’s former employer got wind of his plans and beat him to press in early 1936 with a rival called News Review.

Time didn’t lose much sleep over either imitator, though it did call them “frankly plagiarizing” in a story on their launch. It was especially cutting about Cavalcade’s “casual way of commenting on the parallel” in its first issue: The only mention of Time was a footnote blandly calling it “a news-magazine published in the United States.'” As a news-magazine published in Great Britain, Cavalcade lasted about two years, then became a newsprint tabloid. News Review also grew less like Time over the years and ran out of the same in 1950.

Publications that wouldn’t hesitate to sic the law on imitators tend to tolerate parodists because it makes them seem good sports, because parodists aren’t rich, and because parodies usually have the word PARODY printed on them in great big type. Unlike copycats, parodists want buyers to know they’re getting a spoof — especially if the spoof costs more than the real thing. (In 1982, some newsstands mistakenly sold the $2.00 “Off The Wall Street Journal” as the real Journal, price 50 cents.) Most importantly, parodies are one-shots, usually gone by the time the Real Thing’s next issue hits the stands. But when they’re done right, one is enough. — VCR

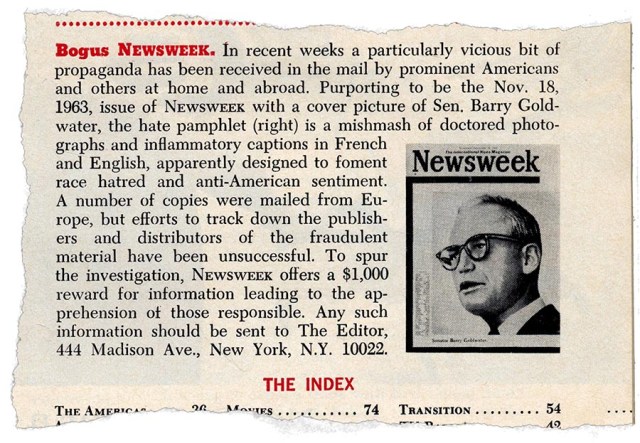

Of all the magazine parodies I’ve heard of but never seen, 1963’s anonymous “Newsweek International Edition” is the most puzzling. Calling it “a vicious piece of propaganda,” the real Newsweek for January 13, 1964, laid out the few facts available: “Purporting to be the Nov. 18, 1963, issue of Newsweek with a cover picture of Sen. Barry Goldwater, the hate pamphlet is a mishmash of doctored photographs and inflammatory captions in French and English, apparently designed to foment race hatred and anti-American sentiment. A number of copies were mailed from Europe, but efforts to track down the publishers and distributors have been unsuccessful.”

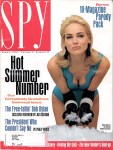

Of all the magazine parodies I’ve heard of but never seen, 1963’s anonymous “Newsweek International Edition” is the most puzzling. Calling it “a vicious piece of propaganda,” the real Newsweek for January 13, 1964, laid out the few facts available: “Purporting to be the Nov. 18, 1963, issue of Newsweek with a cover picture of Sen. Barry Goldwater, the hate pamphlet is a mishmash of doctored photographs and inflammatory captions in French and English, apparently designed to foment race hatred and anti-American sentiment. A number of copies were mailed from Europe, but efforts to track down the publishers and distributors have been unsuccessful.” I’m more confident that whoever created this “Newsweek” either hadn’t seen the original recently or assumed potential readers hadn’t. The cover resembles a typical Newsweek from 1949 or ’50, when its lopsided-red-border-and-square-photo format was new and not yet plastered with boxes and banners. Newsweek began stripping away this effluvia in 1961 and by mid-’62 was running full-bleed covers topped only by its underlined name, as in the real November 18, 1963, issue shown here. Whatever his(?) talents as a propagandist, the creator of “Newsweek” was no great shakes as a parodist. — VCR

I’m more confident that whoever created this “Newsweek” either hadn’t seen the original recently or assumed potential readers hadn’t. The cover resembles a typical Newsweek from 1949 or ’50, when its lopsided-red-border-and-square-photo format was new and not yet plastered with boxes and banners. Newsweek began stripping away this effluvia in 1961 and by mid-’62 was running full-bleed covers topped only by its underlined name, as in the real November 18, 1963, issue shown here. Whatever his(?) talents as a propagandist, the creator of “Newsweek” was no great shakes as a parodist. — VCR